Friday, November 11, 2011

Monday, November 7, 2011

Friday, October 21, 2011

October 21: Pandora's Box/Die Büchse der Pandora (1929 -- G. W. Pabst

★★★★★

The first time I saw Pandora’s Box years ago, what most impressed me was Brooks’ performance and G.W. Pabst’s direction. On this viewing, I saw I was right about both.

Louise Brooks is luminous in this film, and her creation of Lulu is the perfect marriage of artist with medium. Lulu is irrepressibly ebullient, facing problem after problem with a beautiful smile and enthusiastically open arms. Brooks’ Lulu draws everyone she meets to her, and she trusts everyone because no one can resist her. She claps her hands and stands on her tiptoes, and she wins the heart of everyone she meets, from the newspaper editor Schon to Alwa and Countess Geschwitz.

But like her namesake in the movie title, Lulu’s libertine approach to life leads to disaster for most of those who love her. Schon is killed in a jealous struggle, Alwa sinks into poverty providing for her, and Countess Geschwitz loses her money and becomes involved in gambling/murder scene trying to save Lulu from enslavement to an Egyptian. Lulu is magnetic – even to the viewer – but she draws her admirers to certain disaster.

I was right about Pabst’s direction, too. Pandora’s Box moves fast and engages the audience at every point. The film is divided into eight “acts,” each with its individual, self-contained content and arc. Act 3, the “theater” scene, is an absolute directorial tour-de-force. Hordes of exotic, colorful members of a variety revue run into and exit the frame as Lulu, Schon and his fiancé are interacting backstage. Walking among the scantily-clad girls, the Roman strongmen, and the magicians, the stage manager ushers characters on and off stage, all the while trying to eat a sandwich. The choreography here amazes, the camera makes small moves, and the scene gets continuity by following the harried stage manager through all this visual richness.

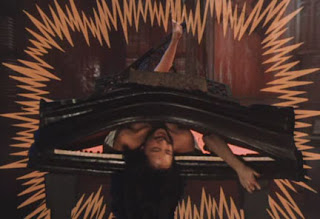

I was right about Pabst’s direction, too. Pandora’s Box moves fast and engages the audience at every point. The film is divided into eight “acts,” each with its individual, self-contained content and arc. Act 3, the “theater” scene, is an absolute directorial tour-de-force. Hordes of exotic, colorful members of a variety revue run into and exit the frame as Lulu, Schon and his fiancé are interacting backstage. Walking among the scantily-clad girls, the Roman strongmen, and the magicians, the stage manager ushers characters on and off stage, all the while trying to eat a sandwich. The choreography here amazes, the camera makes small moves, and the scene gets continuity by following the harried stage manager through all this visual richness. Pabst’s direction is also particularly visible in the action surrounding a bas-relief in Schon’s bedroom. Pabst uses the bas-relief, a particularly ugly rectangle portraying a man grasping upwards, in several different ways, each time picking up on some aspect of the artwork to serve his story. Lit and shot from the side as Lulu and Schon begin their struggle, the bas-relief almost seems a participant with its gesture. And when the struggle intensifies, Pabst’s camera moves up, the lighting shifts and shows the sculpture grasping as the two antagonists struggle for the gun. After Schon is shot, the lighting shifts again, and pained face on the figure emphases the tragedy that has just occurred. But Pabst isn’t finished with the bas-relief at this point; in the next act, Alwa throws his hat towards Lulu, and sculpture appears to be reaching to catch it. Pabst gets so much out of this bas-relief by placing his actors and moving the lighting and camera. Pure directorial flair.

In fact, Pandora’s Box is a beautiful film to watch. Pabst’s frame is always full of visual information. Starting with the beautiful Deco fireplace that opens the film and going through the pageantry of the variety show, the stylish mourning garb Lulu wears to the trial, the variety of characters that gamble on the Italian boat, and the canted angles of the London apartment, the frame of Pandora’s Box always has something interesting to look at.

German Expressionism was still a vital part of film visuals in 1929, and threatening shadows loom behind characters in Pandora’s Box. Murky fog fills the streets of London, obscuring people and places while Jack-the-Ripper wanders loose, and shadow-cut smoke fills the gambling den as Alwa tries to win enough money to save Lulu. Close-ups highlight the exaggerated emotion of silent film, and strong shadows often cut across the actors’ faces or loom behind them. And the camera moves, too, dropping to distort the characters or rising to dominate them. Light and camera are notably purposeful here.

German Expressionism was still a vital part of film visuals in 1929, and threatening shadows loom behind characters in Pandora’s Box. Murky fog fills the streets of London, obscuring people and places while Jack-the-Ripper wanders loose, and shadow-cut smoke fills the gambling den as Alwa tries to win enough money to save Lulu. Close-ups highlight the exaggerated emotion of silent film, and strong shadows often cut across the actors’ faces or loom behind them. And the camera moves, too, dropping to distort the characters or rising to dominate them. Light and camera are notably purposeful here. The story is a strength, too. Of course, it creates one of film’s most memorable characters in Lulu, but it adds depth to her by using the father as a major element. Although Schigolch never approaches Lulu in attractiveness, Lulu has clearly gotten part of her bon vivant attitude from him. He’s always ready to have a drink and make merry just as she’s irrepressibly positive. And he’s there for her when she needs him. The story also uses elements of Weimar life that would soon be removed from film by fascism and the Hays Code. Pandora’s Box has an assembly of feckless characters who frankly engage in prostitution, gambling, seduction for money and drinking. A lesbian like Countess Geschwitz wouldn’t reappear in cinema for decades. Even the (male) camera indulges in this license, lingering on women’s legs and breasts. This story creates a wonderful, intriguing world.

The story is a strength, too. Of course, it creates one of film’s most memorable characters in Lulu, but it adds depth to her by using the father as a major element. Although Schigolch never approaches Lulu in attractiveness, Lulu has clearly gotten part of her bon vivant attitude from him. He’s always ready to have a drink and make merry just as she’s irrepressibly positive. And he’s there for her when she needs him. The story also uses elements of Weimar life that would soon be removed from film by fascism and the Hays Code. Pandora’s Box has an assembly of feckless characters who frankly engage in prostitution, gambling, seduction for money and drinking. A lesbian like Countess Geschwitz wouldn’t reappear in cinema for decades. Even the (male) camera indulges in this license, lingering on women’s legs and breasts. This story creates a wonderful, intriguing world.And like Weimar itself, the story comes to a sad end. Reduced to abject poverty in London, Lulu turns tricks to support herself, Alwa and Schigolch. The last trick she picks up turns out to be penniless, but she flashes her trademark smile as her irrepressible generosity of spirit asserts itself, and she takes the man to the apartment anyway as Alwa suffers mental anguish below. The trick turns out to be Jack the Ripper, and he kills Lulu. As she is dying upstairs, the tormented Alwa, unaware of what has happened, abandons her and seeks salvation from his life by following a Salvation Army Christmas parade. The levels of irony and melodrama in this closing scene give Pandora’s Box just the ending punch it deserves.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

October 20: Modern Times (1936 -- Charlie Chaplin)

★★★★★

As serious as its ideas sound, Modern Times has a sweet, romantic, poignant heart. The Gamine and the Tramp share the fantasy of having a house and living together, and they pursue this fantasy in several episodes. The Gamine finds a warfside shack to role-play a happy couple in a nice house, and a little slapstick lightens the reality of the shack’s inadequacy. The couple then pursues its fantasy when the Tramp gets a job as a department store night watchman and the two can act out married bliss in the store’s furniture section until, once again, reality interrupts and they get thrown out. And there’s a delightful house fantasy with the two waking up in the morning, picking fruit from a branch that comes in through a window and milking a cow that obligingly stops by the door. Not only is this scene romantic as the couple’s ideal, but its over-the-top fantasy feels slightly of irony. It’s poignant to see the ideal of the two determined lovers continually snatched away from them.

As serious as its ideas sound, Modern Times has a sweet, romantic, poignant heart. The Gamine and the Tramp share the fantasy of having a house and living together, and they pursue this fantasy in several episodes. The Gamine finds a warfside shack to role-play a happy couple in a nice house, and a little slapstick lightens the reality of the shack’s inadequacy. The couple then pursues its fantasy when the Tramp gets a job as a department store night watchman and the two can act out married bliss in the store’s furniture section until, once again, reality interrupts and they get thrown out. And there’s a delightful house fantasy with the two waking up in the morning, picking fruit from a branch that comes in through a window and milking a cow that obligingly stops by the door. Not only is this scene romantic as the couple’s ideal, but its over-the-top fantasy feels slightly of irony. It’s poignant to see the ideal of the two determined lovers continually snatched away from them.

This movie is fun, and it’s very sweet. And it also seems very ideological to me. And if I’m going to be preached to, I find the humor and romance here to be at least as engaging as the serious, emotional approach of Potemkin if not more so.

The center of the ideological content here is the Little Tramp, and I commend Chaplin for his insistence that the Little Tramp not speak in this, the character’s last film. The Tramp really is an Everyman, and I get how voice would have lent too much specificity to the character and reduced the range of those who would identify with him. Mime creation that he is, the Tramp is still for each viewer to follow by filling in his own details. The lack of voice is an asset in the rhetorical structure here.

The Everyman Tramp critiques industrialization in a way that seems very much of its time. Critics from the onset of the Industrial Revolution condemned the dehumanization of assembly line work, but the two factory episodes in Modern Times create some of the strongest visual metaphors for this idea. The most memorable, of course, is the brief scene where the Tramp is circulating around the big gears of a machine, though the Tramp’s twitch after his time on the assembly line is as big a critique since it suggests that workers could almost suffer PTS as a result of the dull repetition of their labor. But the twitch doesn’t communicate as effectively in print as stills of the cogs grinding Charlie. And this critique, like the effort to mechanize worker feeding for the sake of efficiency, is muted in the film by comedy, though few 30s leftists would have failed to sympathize with the indictment of factory work.

Other critiques of capital and power are in evidence here, too. The manager is always wanting to increase production speed, whether the workers can keep up or not; he even surveys the bathroom to ensure no one is goofing there. The very suggestion of being a leftist –something like holding a red handkerchief – is enough to land the Tramp in jail, and as the Gamine discovers, labor protests can be fatal. Her father is such a victim. Also, the middle and upper classes are allied with power against the poor here. The hungry Gamine steals bananas for poor and hungry children only to face the boatman’s wrath, and a well-to-do bystander insists that the police take the Gamine to jail for the theft of a loaf of bread although the police already have a suspect, the Tramp. The world of Modern Times is one where workers and the poor are abused and held in check by the power of the more moneyed classes.

As serious as its ideas sound, Modern Times has a sweet, romantic, poignant heart. The Gamine and the Tramp share the fantasy of having a house and living together, and they pursue this fantasy in several episodes. The Gamine finds a warfside shack to role-play a happy couple in a nice house, and a little slapstick lightens the reality of the shack’s inadequacy. The couple then pursues its fantasy when the Tramp gets a job as a department store night watchman and the two can act out married bliss in the store’s furniture section until, once again, reality interrupts and they get thrown out. And there’s a delightful house fantasy with the two waking up in the morning, picking fruit from a branch that comes in through a window and milking a cow that obligingly stops by the door. Not only is this scene romantic as the couple’s ideal, but its over-the-top fantasy feels slightly of irony. It’s poignant to see the ideal of the two determined lovers continually snatched away from them.

As serious as its ideas sound, Modern Times has a sweet, romantic, poignant heart. The Gamine and the Tramp share the fantasy of having a house and living together, and they pursue this fantasy in several episodes. The Gamine finds a warfside shack to role-play a happy couple in a nice house, and a little slapstick lightens the reality of the shack’s inadequacy. The couple then pursues its fantasy when the Tramp gets a job as a department store night watchman and the two can act out married bliss in the store’s furniture section until, once again, reality interrupts and they get thrown out. And there’s a delightful house fantasy with the two waking up in the morning, picking fruit from a branch that comes in through a window and milking a cow that obligingly stops by the door. Not only is this scene romantic as the couple’s ideal, but its over-the-top fantasy feels slightly of irony. It’s poignant to see the ideal of the two determined lovers continually snatched away from them. The end of the film is certainly the least ideological element of Modern Times and makes the best case for those who want to deny the ideology at the core of the movie. As the finally-defeated Gamine asks in frustration, “What’s the use of trying?”, the Tramp tells her to “Buck up!” as the music of “Smile” rises in the background. The two march off into the horizon with the sweet music as a balm to their troubles. No calls for revolution or proletariat uprisings at the end of this film; Modern Times is an early instance of the Hollywood romantic ending blunting a strong socio-economic critique. And yet, the strong poignancy of the film’s ending stems precisely from the viewer knowing the almost impossible odds the two are marching off to confront. On some level, this seeming copout is itself a critique, calling for us to pity the ever-defeated, working class characters as they set out to continue their fight against overwhelming forces.

Modern Times makes timeless entertainment out of strong social criticism.

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

October 19: The Battleship Potemkin (1925 -- Sergei Eisenstein)

★★★★★

Potemkin is a great film that moves me every time I see it.

Everyone knows it for its success as a technical achievement, one of the best and most thorough uses of montage. On this viewing, as always, I loved the way montage makes the lion statues stand to alert as the bombardment starts and the way the solders seem to march relentlessly for miles as they descend the Odessa steps. This time through, I was also more aware of how Eisenstein uses montage for other effects, uses we still see today. For example, as the Potemkin approaches the fleet at the end, the takes get shorter and shorter as the film cuts back and forth between the ship and the fleet, building suspense using faster montage. Likewise, as mutiny builds on the Potemkin earlier in the film, the cutting gets faster and faster. In fact, I even noticed a large, rhythmic pattern in parts like the scenes before and the scenes during the Odessa steps sequence. This film’s tour de force editing gets me every time I see it.

Now I’m cluing in on other things I like about the film, too. An insight this time is that Potemkin is about collective action, and that’s a theme I always respond to personally. It’s a 100% personality bias, but I like movies about teams, groups or, in this case, crews and citizenry. I always connect with seeing a collective come together and mobilize; I respond to portrayals of groups acting with a shared will. What’s interesting here is that we don’t have a team coming together and setting out to accomplish a mission like, say, in Seven Samurai. There are almost no individuals here at all. This is a mass movement filmed as a mass movement, the frequent silent-aesthetic close-ups notwithstanding. And I still wanted to support those sailors and face up to the Czar’s troops.

Now I’m cluing in on other things I like about the film, too. An insight this time is that Potemkin is about collective action, and that’s a theme I always respond to personally. It’s a 100% personality bias, but I like movies about teams, groups or, in this case, crews and citizenry. I always connect with seeing a collective come together and mobilize; I respond to portrayals of groups acting with a shared will. What’s interesting here is that we don’t have a team coming together and setting out to accomplish a mission like, say, in Seven Samurai. There are almost no individuals here at all. This is a mass movement filmed as a mass movement, the frequent silent-aesthetic close-ups notwithstanding. And I still wanted to support those sailors and face up to the Czar’s troops.

My least favorite part of Potemkin has always been the middle part -- A Dead Man Calls for Justice – perhaps because the Drama on the Deck and Odessa Steps sections bookend it and those are two action-packed parts. But knowing the two bookends well this time around, I paid more attention to this slow part on this viewing, and I enjoyed it. There are artfully composed images of long lines of people going to the pier, some walking on an elevated path while others walk along the foreground. These images reminded me of we would find 20 years later in Ivan the Terrible with its artful lines of people curving into the background and made me think such composition is a part of the Eisenstein film vocabulary. I’ll have to watch for it in other films of his. And as I watched the citizenry of Odessa rise in support of the sailors after viewing Vakulinchuk’s body, I was immediately reminded of a story by Garcia Marquez: "The Handsomest Dead Man in the World." In the story, a body washes up on a beach, and as the villagers begin to take care of it, they become more aware of how they’re living and begin to change their drab, routine world; when the citizens find Vakulinchuk’s body, they too begin to realize the repressive forces that are holding them and begin to move toward renewal. I have to wonder if that most leftist of Latin writers Garcia Marquez saw this most leftist of propaganda films and took this section as a spark for a story.

My least favorite part of Potemkin has always been the middle part -- A Dead Man Calls for Justice – perhaps because the Drama on the Deck and Odessa Steps sections bookend it and those are two action-packed parts. But knowing the two bookends well this time around, I paid more attention to this slow part on this viewing, and I enjoyed it. There are artfully composed images of long lines of people going to the pier, some walking on an elevated path while others walk along the foreground. These images reminded me of we would find 20 years later in Ivan the Terrible with its artful lines of people curving into the background and made me think such composition is a part of the Eisenstein film vocabulary. I’ll have to watch for it in other films of his. And as I watched the citizenry of Odessa rise in support of the sailors after viewing Vakulinchuk’s body, I was immediately reminded of a story by Garcia Marquez: "The Handsomest Dead Man in the World." In the story, a body washes up on a beach, and as the villagers begin to take care of it, they become more aware of how they’re living and begin to change their drab, routine world; when the citizens find Vakulinchuk’s body, they too begin to realize the repressive forces that are holding them and begin to move toward renewal. I have to wonder if that most leftist of Latin writers Garcia Marquez saw this most leftist of propaganda films and took this section as a spark for a story.

It was great to revisit this film. The new blu-ray release from Kino has some scenes I definitely hadn't remembered, scenes that make the Czarist troops even more vile. I was struck by the brutality of some of the images in the Steps sequence. But I think these scenes just add to the power of this great movie. Watching Battleship Potemkin., again, I enjoyed it again. I like its themes, I like its technique. What a classic.

Potemkin is a great film that moves me every time I see it.

Everyone knows it for its success as a technical achievement, one of the best and most thorough uses of montage. On this viewing, as always, I loved the way montage makes the lion statues stand to alert as the bombardment starts and the way the solders seem to march relentlessly for miles as they descend the Odessa steps. This time through, I was also more aware of how Eisenstein uses montage for other effects, uses we still see today. For example, as the Potemkin approaches the fleet at the end, the takes get shorter and shorter as the film cuts back and forth between the ship and the fleet, building suspense using faster montage. Likewise, as mutiny builds on the Potemkin earlier in the film, the cutting gets faster and faster. In fact, I even noticed a large, rhythmic pattern in parts like the scenes before and the scenes during the Odessa steps sequence. This film’s tour de force editing gets me every time I see it.

Now I’m cluing in on other things I like about the film, too. An insight this time is that Potemkin is about collective action, and that’s a theme I always respond to personally. It’s a 100% personality bias, but I like movies about teams, groups or, in this case, crews and citizenry. I always connect with seeing a collective come together and mobilize; I respond to portrayals of groups acting with a shared will. What’s interesting here is that we don’t have a team coming together and setting out to accomplish a mission like, say, in Seven Samurai. There are almost no individuals here at all. This is a mass movement filmed as a mass movement, the frequent silent-aesthetic close-ups notwithstanding. And I still wanted to support those sailors and face up to the Czar’s troops.

Now I’m cluing in on other things I like about the film, too. An insight this time is that Potemkin is about collective action, and that’s a theme I always respond to personally. It’s a 100% personality bias, but I like movies about teams, groups or, in this case, crews and citizenry. I always connect with seeing a collective come together and mobilize; I respond to portrayals of groups acting with a shared will. What’s interesting here is that we don’t have a team coming together and setting out to accomplish a mission like, say, in Seven Samurai. There are almost no individuals here at all. This is a mass movement filmed as a mass movement, the frequent silent-aesthetic close-ups notwithstanding. And I still wanted to support those sailors and face up to the Czar’s troops.  My least favorite part of Potemkin has always been the middle part -- A Dead Man Calls for Justice – perhaps because the Drama on the Deck and Odessa Steps sections bookend it and those are two action-packed parts. But knowing the two bookends well this time around, I paid more attention to this slow part on this viewing, and I enjoyed it. There are artfully composed images of long lines of people going to the pier, some walking on an elevated path while others walk along the foreground. These images reminded me of we would find 20 years later in Ivan the Terrible with its artful lines of people curving into the background and made me think such composition is a part of the Eisenstein film vocabulary. I’ll have to watch for it in other films of his. And as I watched the citizenry of Odessa rise in support of the sailors after viewing Vakulinchuk’s body, I was immediately reminded of a story by Garcia Marquez: "The Handsomest Dead Man in the World." In the story, a body washes up on a beach, and as the villagers begin to take care of it, they become more aware of how they’re living and begin to change their drab, routine world; when the citizens find Vakulinchuk’s body, they too begin to realize the repressive forces that are holding them and begin to move toward renewal. I have to wonder if that most leftist of Latin writers Garcia Marquez saw this most leftist of propaganda films and took this section as a spark for a story.

My least favorite part of Potemkin has always been the middle part -- A Dead Man Calls for Justice – perhaps because the Drama on the Deck and Odessa Steps sections bookend it and those are two action-packed parts. But knowing the two bookends well this time around, I paid more attention to this slow part on this viewing, and I enjoyed it. There are artfully composed images of long lines of people going to the pier, some walking on an elevated path while others walk along the foreground. These images reminded me of we would find 20 years later in Ivan the Terrible with its artful lines of people curving into the background and made me think such composition is a part of the Eisenstein film vocabulary. I’ll have to watch for it in other films of his. And as I watched the citizenry of Odessa rise in support of the sailors after viewing Vakulinchuk’s body, I was immediately reminded of a story by Garcia Marquez: "The Handsomest Dead Man in the World." In the story, a body washes up on a beach, and as the villagers begin to take care of it, they become more aware of how they’re living and begin to change their drab, routine world; when the citizens find Vakulinchuk’s body, they too begin to realize the repressive forces that are holding them and begin to move toward renewal. I have to wonder if that most leftist of Latin writers Garcia Marquez saw this most leftist of propaganda films and took this section as a spark for a story. It was great to revisit this film. The new blu-ray release from Kino has some scenes I definitely hadn't remembered, scenes that make the Czarist troops even more vile. I was struck by the brutality of some of the images in the Steps sequence. But I think these scenes just add to the power of this great movie. Watching Battleship Potemkin., again, I enjoyed it again. I like its themes, I like its technique. What a classic.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Monday, October 17, 2011

October 17: House/Hausu (1977 -- Nobuhiko Ohbayashi)

★★★

But the sheer imagination in the film is the element I like the most about it. Not only was I unable to anticipate what would happen from scene to scene, but I couldn’t even anticipate what was going to happen from one moment to the next inside a single scene. When Fantasy discovers Mac’s severed head in the well, the scared girl throws the head back in and quickly turns around to another task. No surprise there. But Mac’s disembodied head then floats out of the well behind the girl and, after a couple of aerial flourishes, descends to the unaware Fantasy and bites her in the ass. Later, the teacher/rescuer horrifies the watermelon farmer by wanting a banana, and when we next see the teacher’s car, the teacher has become a life-sized stack of bananas. House has a staggering inventiveness that never seems to refer to conventional thought.

But the sheer imagination in the film is the element I like the most about it. Not only was I unable to anticipate what would happen from scene to scene, but I couldn’t even anticipate what was going to happen from one moment to the next inside a single scene. When Fantasy discovers Mac’s severed head in the well, the scared girl throws the head back in and quickly turns around to another task. No surprise there. But Mac’s disembodied head then floats out of the well behind the girl and, after a couple of aerial flourishes, descends to the unaware Fantasy and bites her in the ass. Later, the teacher/rescuer horrifies the watermelon farmer by wanting a banana, and when we next see the teacher’s car, the teacher has become a life-sized stack of bananas. House has a staggering inventiveness that never seems to refer to conventional thought.

House is one of the most unique films I’ve ever seen if not the most unique. I think of Japanese culture in general as having a flair for style, but House is style to the nth.

From the moment the film starts with its cute (Spice) Girls saying cute, artificial lines and wearing cute, stylized clothes until the film moves on to the girls’ stylized demises as they are eaten by a lampshade, consumed by a piano or decapitated in a well, House is an outrageous, psychedelic race from one unexpected event to the other. Gorgeous’ father introduces his new fiancé, and the woman is bathed in soft light as her scarf flutters languidly behind her. She almost floats over to her stepdaughter-to-be. The entire movie is one stylization after another.

But the sheer imagination in the film is the element I like the most about it. Not only was I unable to anticipate what would happen from scene to scene, but I couldn’t even anticipate what was going to happen from one moment to the next inside a single scene. When Fantasy discovers Mac’s severed head in the well, the scared girl throws the head back in and quickly turns around to another task. No surprise there. But Mac’s disembodied head then floats out of the well behind the girl and, after a couple of aerial flourishes, descends to the unaware Fantasy and bites her in the ass. Later, the teacher/rescuer horrifies the watermelon farmer by wanting a banana, and when we next see the teacher’s car, the teacher has become a life-sized stack of bananas. House has a staggering inventiveness that never seems to refer to conventional thought.

But the sheer imagination in the film is the element I like the most about it. Not only was I unable to anticipate what would happen from scene to scene, but I couldn’t even anticipate what was going to happen from one moment to the next inside a single scene. When Fantasy discovers Mac’s severed head in the well, the scared girl throws the head back in and quickly turns around to another task. No surprise there. But Mac’s disembodied head then floats out of the well behind the girl and, after a couple of aerial flourishes, descends to the unaware Fantasy and bites her in the ass. Later, the teacher/rescuer horrifies the watermelon farmer by wanting a banana, and when we next see the teacher’s car, the teacher has become a life-sized stack of bananas. House has a staggering inventiveness that never seems to refer to conventional thought.Throughout the film, I tried to get a grasp on where this movie might be coming from. There’s certainly a little of the The Monkees TV show or Sgt. Pepper’s. Some of the more horrific elements echo Monty Python or Dario Argento. But House is one of a kind, and though its consistent tone eventually runs a little slow over the course of 90 minutes, it’s still 90 minutes of some of the most inventive experiment I’ve seen. The perfect Halloween flic.

Later note: Koganada's short, Trick or Truth, adds an important element to an understanding of this film. There's more than just flash to Ohbayashi's work. (http://kogonada.com/portfolio/trick-or-truth)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)