Saturday, December 31, 2011

Friday, December 30, 2011

Thursday, December 29, 2011

Friday, December 23, 2011

Thursday, December 22, 2011

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

Tuesday, December 13, 2011

Monday, December 12, 2011

December 12: Kiss Me Deadly (1955 -- Robert Aldrich)

★★★★

The line on this movie is that it’s subversive, subverting noir, the Spillane character, and the Board of Censors. Even film credits. But it doesn’t seem subversive to me as much as hostile. The film seems to attack all these, stretching and deforming them. I don’t think Kiss Me Deadly is calling for a new form of film narrative; I think it’s slashing at the one it’s using. And its genre-bashing is a big part of what makes it worthwhile.

The Spillane character here is both inept and deplorable. Fifteen years before, Sam Spade didn’t mind tricking people or sometimes bullying them, but he’s an angel compared to Mike Hammer, who repeatedly bashes one man’s head into a building, bullies a weakling father into confession in front of his family, and crushes a coroner’s hand in a drawer and holds it there. This detective is exponentially more corrupt that Sam Spade , too. Private detective Sam makes his money by solving cases and thinks he can make a profit by recovering the Maltese falcon, but Hammer generally lives by getting a contract with a wife and having his partner, Velda, then seduce the husband to facilitate things. Even the secretarial sidekick is intensified in Kiss Me Deadly. Effie is the prim, loyal secretary to Sam, but Velda is a sexpot dressed in tight sweaters who’s regularly throwing herself at Hammer. It’s hard to imagine the faithful Effie slinking around a pole, sweating, and extending her legs toward Sam Spade, not to mention that we wouldn’t see Sam talking to her in bed while she’s recovering from a hangover. Kiss Me Deadly stretches and distorts the basic noir elements of detective and his girl.

There’s not much the film can do to exaggerate the typical noir shadows and low-angle shots, but Kiss Me Deadly amply appropriates them. And in an almost Expressionist gesture, the camera often takes the position of an interlocutor, and we find ourselves nose-to-nose with a grimace or seeing a fist heading our direction. These flourishes increase our self-consciousness about the film.

Kiss Me Deadly also amps up noir’s stakes. There may be some dark plot behind noir intrigue, but the end of Kiss Me Deadly becomes science fiction when the conspiracy leads Hammer to the sought-after box and we discover the box could actually end the world. Flesh is seared and buildings destroyed in this film as noir morphs into paranoid 50s sci fi at the end. This is no longer film noir.

There are many things to appreciate in this film. Many of the images are memorable and in-your-face, such as the one where Lily sits behind a stack of suitcases and we see only the suitcases with her feet sticking out from behind. And there are, in fact, numerous shots of shoes, feet and legs that the film uses to suggest entire characters (it’s not hard to image that Koreyoshi Kurahara found the trench coats and feet for his 1957 I Am Waiting in this film).

But as much as I like it, this film leaves me with a slight touch of disappointment. It shares the strange, twisted spirit of other mid-50s movies like Bigger than Life and Night of the Hunter, but Kiss Me Deadly gets quite close to parody if not actually crossing that line at times. Night of the Hunter cites German Expressionism very self-consciously, but it uses that vocabulary to talk about human experience and to touch the viewer; Kiss Me Deadly, though, seems more concerned with self-referentiality than with life, and as it deforms and intensifies noir, it doesn’t connect with me on much more than an intellectual level. It’s a very good film with many engaging flourishes, but I found it a little more interested in form than in the heart.

Thursday, December 8, 2011

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Thursday, December 1, 2011

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Saturday, November 19, 2011

Friday, November 18, 2011

November 18: Nosferatu (1922 -- F.W. Murnau)

A year after the Phantom Carriage, European audiences would have seen this triumph of Expressionist mood. Carriage works in the space where the natural and supernatural interface; Nosferatu lives in a separate, non-natural world. Everyday people die and their souls are collected in Sweden, but in Wisborg, real estate agents read occult glyphs, women bond with their husbands via ESP, and rat-toothed undead strive to extend their geographic reach. Nosferatu takes place in a silent, threatening, Expressionist realm where vampires are real.

Murnau manages to tie a lot of disparate elements together to create his nightmare. The world of Nosferatu conflates vampire imagery – coffins, stiff movement, big teeth, corpses with long fingernails – and imagery of rats, who have long, menacing front incisors and are themselves linked to darkness and decay. And this web of images naturally expands to include the Plague, spread by rats and leading to death. It’s an effective set of imagery with a strong affinity.

There are powerful cinematic elements in Nosferatu that reinforce the web of creepy imagery. The unnatural coach arrives and departs in fast motion, and during its voyage, the countryside loses its substantiality as the film stock goes from positive to negative and the sky becomes solid, the landscape clear. Max Schreck’s Nosferatu is a corpse that has lost the agility of life. He moves slowly and stiffly, bending his dead, stiffened joints only as much as locomotion requires. His over-stuffed back and tiny lower body are otherworldly, and his white make-up and long fingernails hearken back to the features of a corpse. And his long ears and rat/vampire front teeth link him to the animal world and to the world of the dead. The acting and prosthetics here work in fine harmony to the rest of the imagery.

There are powerful cinematic elements in Nosferatu that reinforce the web of creepy imagery. The unnatural coach arrives and departs in fast motion, and during its voyage, the countryside loses its substantiality as the film stock goes from positive to negative and the sky becomes solid, the landscape clear. Max Schreck’s Nosferatu is a corpse that has lost the agility of life. He moves slowly and stiffly, bending his dead, stiffened joints only as much as locomotion requires. His over-stuffed back and tiny lower body are otherworldly, and his white make-up and long fingernails hearken back to the features of a corpse. And his long ears and rat/vampire front teeth link him to the animal world and to the world of the dead. The acting and prosthetics here work in fine harmony to the rest of the imagery.Nosferatu's animal world, in fact, is menacing and threatening,. At one point, the film shifts to a biology class where the students watch a Venus Fly-trap catch a victim and a tentacled polyp snare its prey. These digressions hearken to a contemporary interest in short films about the unusual, but they don’t move the story forward at all. Their main function in the film is to work with the rest of the predator/prey and death imagery. If such plants hadn’t exist, Expressionism would have invented them for this movie.

Watching Nosferatu, I remain in awe of how quickly film language developed. With no zoom lens or concept of it, Murnau uses the iris to focus audience attention when he wants to. And while Sjöström had used editing for flashbacks, Murnau uses it to create montages of simultaneous actions (Ellen worries while Thomas suffers; Orlok and Hutter travel at the same time on different routes). Eisenstein would soon find other applications for montage. And Expressionism made ample use of exaggerated lighting. Some of the strongest images in Nosferatu are silhouettes of the vampire.

We don’t have the original music, but I wonder what it would have sounded like. I’ve watched Nosferatu with a full orchestra soundtrack and with an organ soundtrack, and while each has its own strengths, each is also oddly intrusive at times. Given how meticulous Murnau was about all the detail in this film, I wonder what the experience would be of watching it with the music Murnau preferred.

It’s the creepy artifice of Nosferatu that makes it such a great film, and that’s why we can still enjoy it today. Murnau mustered every element of his medium that he could imagine in service to the effect he wanted. And we have a great work of art to enjoy as a result.

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

November 16: The Phantom Carriage/Körkarlen (1921 -- Victor Sjöström)

I was thinking Halloween movies, so it blindsided me to find that Phantom Carriage is actually a Christmas movie. I didn’t expect to see a hooded figure with a scythe leading a sinner around to confront his malfeasance and get him to repent of his evil ways. Of course, it’s New Year’s here and not Christmas Eve, but that’s mostly because the Swedish legend behind the story requires the sinner, David Holm, to die at midnight on New Year’s Eve in order to become Death’s carriage driver.

One of the most compelling elements here is Holm’s sin, or more to the point, the way Victor Sjöström plays the sinner. Holm loathes everything, including himself. After his first effort at reform fails, he hardens into hatred of his wife, the incorruptible missionary Edit, and himself. He bullies friends when they drink, threatens his wife, and rejects every overture from Edit, even tearing up his jacket after she has mended it. But through all this bombast, Sjöström still manages to create a complex, conflicted human being. I was totally captured by the scene of his tearing up the jacket, and I even felt his wonder and fear as he recognizes Death’s driver and realizes that he’s died.

I was impressed with a lot of the storytelling, too. Phantom Carriage opens with a series of enigmas: Who is the woman dying? Who is the other woman? Who is the woman that the dying wants to see? Who is Mr. Holm? Why are people against her wishes? And I got the answers to these only gradually, staying with the film to find them. I also like the series of flashbacks here. Phantom Carriage uses editing to parse time, and we go from now to the past and back to now, albeit a present in a new location where Holm will meet the carriage driver. There are flashbacks within flashbacks, too, like the sequences of the carriage driver wearily going about his duty of collecting souls. Sjöström has already understood the use of editing to build suspense, too. As Holm is breaking through a door to get at his wife and children, Sjöström cuts rapidly between the huddled family and the furious father.

Of course, the famous special effects here are rightly praised since the double exposures that would have been necessary to get the dead and living in the same frame must have required mind-boggling precision. And they’re genuinely creepy. I got goose bumps watching the carriage drive out over the water so the driver could then pick up the drowned man’s soul, and Matti Bye’s effective score has particular resonance here. As director, Sjöström gives us lots of information in the frame by using deep focus, and his super-realism makes the supernatural elements feel that much more real.

Even without knowing the well-documented links between Phantom Carriage and Bergman, a viewer will certainly notice connections. Death in the Seventh Seal dresses a lot like the driver in Phantom Carriage, and there’s even a shot of the carriage going over a horizon here that looks a lot like the shot at the end of Seventh Seal as Death leads his recruits over a similar hill. Other images from other directors also seem too similar to be coincidental. As I watched Holm take an ax to a door to get to his family, I half expected to hear him say, “Herrrre’s Johnny!” And I’ve yet to see a Ghost of Christmas Future that doesn’t look like the carriage driver either. Even thematically, Edit's passion for David at times trembles at the border boundary of spiritual and carnal, a situation Melville gets much out of in Leon Morin, Priest , though Melville doesn't maintain the tension throughout in the way

There is so much to like here. Victor Sjöström carries the film with his dynamic portrayal of David Holm, and the story and effects make the film even more engaging. The rather saccharine ending – totally expected and totally conventional -- don’t add a lot to Phantom Carriage but are to be somewhat forgiven in 1921. This is a worthwhile experience by any account.

Sunday, November 13, 2011

Friday, November 11, 2011

Monday, November 7, 2011

Friday, October 21, 2011

October 21: Pandora's Box/Die Büchse der Pandora (1929 -- G. W. Pabst

★★★★★

The first time I saw Pandora’s Box years ago, what most impressed me was Brooks’ performance and G.W. Pabst’s direction. On this viewing, I saw I was right about both.

Louise Brooks is luminous in this film, and her creation of Lulu is the perfect marriage of artist with medium. Lulu is irrepressibly ebullient, facing problem after problem with a beautiful smile and enthusiastically open arms. Brooks’ Lulu draws everyone she meets to her, and she trusts everyone because no one can resist her. She claps her hands and stands on her tiptoes, and she wins the heart of everyone she meets, from the newspaper editor Schon to Alwa and Countess Geschwitz.

But like her namesake in the movie title, Lulu’s libertine approach to life leads to disaster for most of those who love her. Schon is killed in a jealous struggle, Alwa sinks into poverty providing for her, and Countess Geschwitz loses her money and becomes involved in gambling/murder scene trying to save Lulu from enslavement to an Egyptian. Lulu is magnetic – even to the viewer – but she draws her admirers to certain disaster.

I was right about Pabst’s direction, too. Pandora’s Box moves fast and engages the audience at every point. The film is divided into eight “acts,” each with its individual, self-contained content and arc. Act 3, the “theater” scene, is an absolute directorial tour-de-force. Hordes of exotic, colorful members of a variety revue run into and exit the frame as Lulu, Schon and his fiancé are interacting backstage. Walking among the scantily-clad girls, the Roman strongmen, and the magicians, the stage manager ushers characters on and off stage, all the while trying to eat a sandwich. The choreography here amazes, the camera makes small moves, and the scene gets continuity by following the harried stage manager through all this visual richness.

I was right about Pabst’s direction, too. Pandora’s Box moves fast and engages the audience at every point. The film is divided into eight “acts,” each with its individual, self-contained content and arc. Act 3, the “theater” scene, is an absolute directorial tour-de-force. Hordes of exotic, colorful members of a variety revue run into and exit the frame as Lulu, Schon and his fiancé are interacting backstage. Walking among the scantily-clad girls, the Roman strongmen, and the magicians, the stage manager ushers characters on and off stage, all the while trying to eat a sandwich. The choreography here amazes, the camera makes small moves, and the scene gets continuity by following the harried stage manager through all this visual richness. Pabst’s direction is also particularly visible in the action surrounding a bas-relief in Schon’s bedroom. Pabst uses the bas-relief, a particularly ugly rectangle portraying a man grasping upwards, in several different ways, each time picking up on some aspect of the artwork to serve his story. Lit and shot from the side as Lulu and Schon begin their struggle, the bas-relief almost seems a participant with its gesture. And when the struggle intensifies, Pabst’s camera moves up, the lighting shifts and shows the sculpture grasping as the two antagonists struggle for the gun. After Schon is shot, the lighting shifts again, and pained face on the figure emphases the tragedy that has just occurred. But Pabst isn’t finished with the bas-relief at this point; in the next act, Alwa throws his hat towards Lulu, and sculpture appears to be reaching to catch it. Pabst gets so much out of this bas-relief by placing his actors and moving the lighting and camera. Pure directorial flair.

In fact, Pandora’s Box is a beautiful film to watch. Pabst’s frame is always full of visual information. Starting with the beautiful Deco fireplace that opens the film and going through the pageantry of the variety show, the stylish mourning garb Lulu wears to the trial, the variety of characters that gamble on the Italian boat, and the canted angles of the London apartment, the frame of Pandora’s Box always has something interesting to look at.

German Expressionism was still a vital part of film visuals in 1929, and threatening shadows loom behind characters in Pandora’s Box. Murky fog fills the streets of London, obscuring people and places while Jack-the-Ripper wanders loose, and shadow-cut smoke fills the gambling den as Alwa tries to win enough money to save Lulu. Close-ups highlight the exaggerated emotion of silent film, and strong shadows often cut across the actors’ faces or loom behind them. And the camera moves, too, dropping to distort the characters or rising to dominate them. Light and camera are notably purposeful here.

German Expressionism was still a vital part of film visuals in 1929, and threatening shadows loom behind characters in Pandora’s Box. Murky fog fills the streets of London, obscuring people and places while Jack-the-Ripper wanders loose, and shadow-cut smoke fills the gambling den as Alwa tries to win enough money to save Lulu. Close-ups highlight the exaggerated emotion of silent film, and strong shadows often cut across the actors’ faces or loom behind them. And the camera moves, too, dropping to distort the characters or rising to dominate them. Light and camera are notably purposeful here. The story is a strength, too. Of course, it creates one of film’s most memorable characters in Lulu, but it adds depth to her by using the father as a major element. Although Schigolch never approaches Lulu in attractiveness, Lulu has clearly gotten part of her bon vivant attitude from him. He’s always ready to have a drink and make merry just as she’s irrepressibly positive. And he’s there for her when she needs him. The story also uses elements of Weimar life that would soon be removed from film by fascism and the Hays Code. Pandora’s Box has an assembly of feckless characters who frankly engage in prostitution, gambling, seduction for money and drinking. A lesbian like Countess Geschwitz wouldn’t reappear in cinema for decades. Even the (male) camera indulges in this license, lingering on women’s legs and breasts. This story creates a wonderful, intriguing world.

The story is a strength, too. Of course, it creates one of film’s most memorable characters in Lulu, but it adds depth to her by using the father as a major element. Although Schigolch never approaches Lulu in attractiveness, Lulu has clearly gotten part of her bon vivant attitude from him. He’s always ready to have a drink and make merry just as she’s irrepressibly positive. And he’s there for her when she needs him. The story also uses elements of Weimar life that would soon be removed from film by fascism and the Hays Code. Pandora’s Box has an assembly of feckless characters who frankly engage in prostitution, gambling, seduction for money and drinking. A lesbian like Countess Geschwitz wouldn’t reappear in cinema for decades. Even the (male) camera indulges in this license, lingering on women’s legs and breasts. This story creates a wonderful, intriguing world.And like Weimar itself, the story comes to a sad end. Reduced to abject poverty in London, Lulu turns tricks to support herself, Alwa and Schigolch. The last trick she picks up turns out to be penniless, but she flashes her trademark smile as her irrepressible generosity of spirit asserts itself, and she takes the man to the apartment anyway as Alwa suffers mental anguish below. The trick turns out to be Jack the Ripper, and he kills Lulu. As she is dying upstairs, the tormented Alwa, unaware of what has happened, abandons her and seeks salvation from his life by following a Salvation Army Christmas parade. The levels of irony and melodrama in this closing scene give Pandora’s Box just the ending punch it deserves.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

October 20: Modern Times (1936 -- Charlie Chaplin)

★★★★★

As serious as its ideas sound, Modern Times has a sweet, romantic, poignant heart. The Gamine and the Tramp share the fantasy of having a house and living together, and they pursue this fantasy in several episodes. The Gamine finds a warfside shack to role-play a happy couple in a nice house, and a little slapstick lightens the reality of the shack’s inadequacy. The couple then pursues its fantasy when the Tramp gets a job as a department store night watchman and the two can act out married bliss in the store’s furniture section until, once again, reality interrupts and they get thrown out. And there’s a delightful house fantasy with the two waking up in the morning, picking fruit from a branch that comes in through a window and milking a cow that obligingly stops by the door. Not only is this scene romantic as the couple’s ideal, but its over-the-top fantasy feels slightly of irony. It’s poignant to see the ideal of the two determined lovers continually snatched away from them.

As serious as its ideas sound, Modern Times has a sweet, romantic, poignant heart. The Gamine and the Tramp share the fantasy of having a house and living together, and they pursue this fantasy in several episodes. The Gamine finds a warfside shack to role-play a happy couple in a nice house, and a little slapstick lightens the reality of the shack’s inadequacy. The couple then pursues its fantasy when the Tramp gets a job as a department store night watchman and the two can act out married bliss in the store’s furniture section until, once again, reality interrupts and they get thrown out. And there’s a delightful house fantasy with the two waking up in the morning, picking fruit from a branch that comes in through a window and milking a cow that obligingly stops by the door. Not only is this scene romantic as the couple’s ideal, but its over-the-top fantasy feels slightly of irony. It’s poignant to see the ideal of the two determined lovers continually snatched away from them.

This movie is fun, and it’s very sweet. And it also seems very ideological to me. And if I’m going to be preached to, I find the humor and romance here to be at least as engaging as the serious, emotional approach of Potemkin if not more so.

The center of the ideological content here is the Little Tramp, and I commend Chaplin for his insistence that the Little Tramp not speak in this, the character’s last film. The Tramp really is an Everyman, and I get how voice would have lent too much specificity to the character and reduced the range of those who would identify with him. Mime creation that he is, the Tramp is still for each viewer to follow by filling in his own details. The lack of voice is an asset in the rhetorical structure here.

The Everyman Tramp critiques industrialization in a way that seems very much of its time. Critics from the onset of the Industrial Revolution condemned the dehumanization of assembly line work, but the two factory episodes in Modern Times create some of the strongest visual metaphors for this idea. The most memorable, of course, is the brief scene where the Tramp is circulating around the big gears of a machine, though the Tramp’s twitch after his time on the assembly line is as big a critique since it suggests that workers could almost suffer PTS as a result of the dull repetition of their labor. But the twitch doesn’t communicate as effectively in print as stills of the cogs grinding Charlie. And this critique, like the effort to mechanize worker feeding for the sake of efficiency, is muted in the film by comedy, though few 30s leftists would have failed to sympathize with the indictment of factory work.

Other critiques of capital and power are in evidence here, too. The manager is always wanting to increase production speed, whether the workers can keep up or not; he even surveys the bathroom to ensure no one is goofing there. The very suggestion of being a leftist –something like holding a red handkerchief – is enough to land the Tramp in jail, and as the Gamine discovers, labor protests can be fatal. Her father is such a victim. Also, the middle and upper classes are allied with power against the poor here. The hungry Gamine steals bananas for poor and hungry children only to face the boatman’s wrath, and a well-to-do bystander insists that the police take the Gamine to jail for the theft of a loaf of bread although the police already have a suspect, the Tramp. The world of Modern Times is one where workers and the poor are abused and held in check by the power of the more moneyed classes.

As serious as its ideas sound, Modern Times has a sweet, romantic, poignant heart. The Gamine and the Tramp share the fantasy of having a house and living together, and they pursue this fantasy in several episodes. The Gamine finds a warfside shack to role-play a happy couple in a nice house, and a little slapstick lightens the reality of the shack’s inadequacy. The couple then pursues its fantasy when the Tramp gets a job as a department store night watchman and the two can act out married bliss in the store’s furniture section until, once again, reality interrupts and they get thrown out. And there’s a delightful house fantasy with the two waking up in the morning, picking fruit from a branch that comes in through a window and milking a cow that obligingly stops by the door. Not only is this scene romantic as the couple’s ideal, but its over-the-top fantasy feels slightly of irony. It’s poignant to see the ideal of the two determined lovers continually snatched away from them.

As serious as its ideas sound, Modern Times has a sweet, romantic, poignant heart. The Gamine and the Tramp share the fantasy of having a house and living together, and they pursue this fantasy in several episodes. The Gamine finds a warfside shack to role-play a happy couple in a nice house, and a little slapstick lightens the reality of the shack’s inadequacy. The couple then pursues its fantasy when the Tramp gets a job as a department store night watchman and the two can act out married bliss in the store’s furniture section until, once again, reality interrupts and they get thrown out. And there’s a delightful house fantasy with the two waking up in the morning, picking fruit from a branch that comes in through a window and milking a cow that obligingly stops by the door. Not only is this scene romantic as the couple’s ideal, but its over-the-top fantasy feels slightly of irony. It’s poignant to see the ideal of the two determined lovers continually snatched away from them. The end of the film is certainly the least ideological element of Modern Times and makes the best case for those who want to deny the ideology at the core of the movie. As the finally-defeated Gamine asks in frustration, “What’s the use of trying?”, the Tramp tells her to “Buck up!” as the music of “Smile” rises in the background. The two march off into the horizon with the sweet music as a balm to their troubles. No calls for revolution or proletariat uprisings at the end of this film; Modern Times is an early instance of the Hollywood romantic ending blunting a strong socio-economic critique. And yet, the strong poignancy of the film’s ending stems precisely from the viewer knowing the almost impossible odds the two are marching off to confront. On some level, this seeming copout is itself a critique, calling for us to pity the ever-defeated, working class characters as they set out to continue their fight against overwhelming forces.

Modern Times makes timeless entertainment out of strong social criticism.

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

October 19: The Battleship Potemkin (1925 -- Sergei Eisenstein)

★★★★★

Potemkin is a great film that moves me every time I see it.

Everyone knows it for its success as a technical achievement, one of the best and most thorough uses of montage. On this viewing, as always, I loved the way montage makes the lion statues stand to alert as the bombardment starts and the way the solders seem to march relentlessly for miles as they descend the Odessa steps. This time through, I was also more aware of how Eisenstein uses montage for other effects, uses we still see today. For example, as the Potemkin approaches the fleet at the end, the takes get shorter and shorter as the film cuts back and forth between the ship and the fleet, building suspense using faster montage. Likewise, as mutiny builds on the Potemkin earlier in the film, the cutting gets faster and faster. In fact, I even noticed a large, rhythmic pattern in parts like the scenes before and the scenes during the Odessa steps sequence. This film’s tour de force editing gets me every time I see it.

Now I’m cluing in on other things I like about the film, too. An insight this time is that Potemkin is about collective action, and that’s a theme I always respond to personally. It’s a 100% personality bias, but I like movies about teams, groups or, in this case, crews and citizenry. I always connect with seeing a collective come together and mobilize; I respond to portrayals of groups acting with a shared will. What’s interesting here is that we don’t have a team coming together and setting out to accomplish a mission like, say, in Seven Samurai. There are almost no individuals here at all. This is a mass movement filmed as a mass movement, the frequent silent-aesthetic close-ups notwithstanding. And I still wanted to support those sailors and face up to the Czar’s troops.

Now I’m cluing in on other things I like about the film, too. An insight this time is that Potemkin is about collective action, and that’s a theme I always respond to personally. It’s a 100% personality bias, but I like movies about teams, groups or, in this case, crews and citizenry. I always connect with seeing a collective come together and mobilize; I respond to portrayals of groups acting with a shared will. What’s interesting here is that we don’t have a team coming together and setting out to accomplish a mission like, say, in Seven Samurai. There are almost no individuals here at all. This is a mass movement filmed as a mass movement, the frequent silent-aesthetic close-ups notwithstanding. And I still wanted to support those sailors and face up to the Czar’s troops.

My least favorite part of Potemkin has always been the middle part -- A Dead Man Calls for Justice – perhaps because the Drama on the Deck and Odessa Steps sections bookend it and those are two action-packed parts. But knowing the two bookends well this time around, I paid more attention to this slow part on this viewing, and I enjoyed it. There are artfully composed images of long lines of people going to the pier, some walking on an elevated path while others walk along the foreground. These images reminded me of we would find 20 years later in Ivan the Terrible with its artful lines of people curving into the background and made me think such composition is a part of the Eisenstein film vocabulary. I’ll have to watch for it in other films of his. And as I watched the citizenry of Odessa rise in support of the sailors after viewing Vakulinchuk’s body, I was immediately reminded of a story by Garcia Marquez: "The Handsomest Dead Man in the World." In the story, a body washes up on a beach, and as the villagers begin to take care of it, they become more aware of how they’re living and begin to change their drab, routine world; when the citizens find Vakulinchuk’s body, they too begin to realize the repressive forces that are holding them and begin to move toward renewal. I have to wonder if that most leftist of Latin writers Garcia Marquez saw this most leftist of propaganda films and took this section as a spark for a story.

My least favorite part of Potemkin has always been the middle part -- A Dead Man Calls for Justice – perhaps because the Drama on the Deck and Odessa Steps sections bookend it and those are two action-packed parts. But knowing the two bookends well this time around, I paid more attention to this slow part on this viewing, and I enjoyed it. There are artfully composed images of long lines of people going to the pier, some walking on an elevated path while others walk along the foreground. These images reminded me of we would find 20 years later in Ivan the Terrible with its artful lines of people curving into the background and made me think such composition is a part of the Eisenstein film vocabulary. I’ll have to watch for it in other films of his. And as I watched the citizenry of Odessa rise in support of the sailors after viewing Vakulinchuk’s body, I was immediately reminded of a story by Garcia Marquez: "The Handsomest Dead Man in the World." In the story, a body washes up on a beach, and as the villagers begin to take care of it, they become more aware of how they’re living and begin to change their drab, routine world; when the citizens find Vakulinchuk’s body, they too begin to realize the repressive forces that are holding them and begin to move toward renewal. I have to wonder if that most leftist of Latin writers Garcia Marquez saw this most leftist of propaganda films and took this section as a spark for a story.

It was great to revisit this film. The new blu-ray release from Kino has some scenes I definitely hadn't remembered, scenes that make the Czarist troops even more vile. I was struck by the brutality of some of the images in the Steps sequence. But I think these scenes just add to the power of this great movie. Watching Battleship Potemkin., again, I enjoyed it again. I like its themes, I like its technique. What a classic.

Potemkin is a great film that moves me every time I see it.

Everyone knows it for its success as a technical achievement, one of the best and most thorough uses of montage. On this viewing, as always, I loved the way montage makes the lion statues stand to alert as the bombardment starts and the way the solders seem to march relentlessly for miles as they descend the Odessa steps. This time through, I was also more aware of how Eisenstein uses montage for other effects, uses we still see today. For example, as the Potemkin approaches the fleet at the end, the takes get shorter and shorter as the film cuts back and forth between the ship and the fleet, building suspense using faster montage. Likewise, as mutiny builds on the Potemkin earlier in the film, the cutting gets faster and faster. In fact, I even noticed a large, rhythmic pattern in parts like the scenes before and the scenes during the Odessa steps sequence. This film’s tour de force editing gets me every time I see it.

Now I’m cluing in on other things I like about the film, too. An insight this time is that Potemkin is about collective action, and that’s a theme I always respond to personally. It’s a 100% personality bias, but I like movies about teams, groups or, in this case, crews and citizenry. I always connect with seeing a collective come together and mobilize; I respond to portrayals of groups acting with a shared will. What’s interesting here is that we don’t have a team coming together and setting out to accomplish a mission like, say, in Seven Samurai. There are almost no individuals here at all. This is a mass movement filmed as a mass movement, the frequent silent-aesthetic close-ups notwithstanding. And I still wanted to support those sailors and face up to the Czar’s troops.

Now I’m cluing in on other things I like about the film, too. An insight this time is that Potemkin is about collective action, and that’s a theme I always respond to personally. It’s a 100% personality bias, but I like movies about teams, groups or, in this case, crews and citizenry. I always connect with seeing a collective come together and mobilize; I respond to portrayals of groups acting with a shared will. What’s interesting here is that we don’t have a team coming together and setting out to accomplish a mission like, say, in Seven Samurai. There are almost no individuals here at all. This is a mass movement filmed as a mass movement, the frequent silent-aesthetic close-ups notwithstanding. And I still wanted to support those sailors and face up to the Czar’s troops.  My least favorite part of Potemkin has always been the middle part -- A Dead Man Calls for Justice – perhaps because the Drama on the Deck and Odessa Steps sections bookend it and those are two action-packed parts. But knowing the two bookends well this time around, I paid more attention to this slow part on this viewing, and I enjoyed it. There are artfully composed images of long lines of people going to the pier, some walking on an elevated path while others walk along the foreground. These images reminded me of we would find 20 years later in Ivan the Terrible with its artful lines of people curving into the background and made me think such composition is a part of the Eisenstein film vocabulary. I’ll have to watch for it in other films of his. And as I watched the citizenry of Odessa rise in support of the sailors after viewing Vakulinchuk’s body, I was immediately reminded of a story by Garcia Marquez: "The Handsomest Dead Man in the World." In the story, a body washes up on a beach, and as the villagers begin to take care of it, they become more aware of how they’re living and begin to change their drab, routine world; when the citizens find Vakulinchuk’s body, they too begin to realize the repressive forces that are holding them and begin to move toward renewal. I have to wonder if that most leftist of Latin writers Garcia Marquez saw this most leftist of propaganda films and took this section as a spark for a story.

My least favorite part of Potemkin has always been the middle part -- A Dead Man Calls for Justice – perhaps because the Drama on the Deck and Odessa Steps sections bookend it and those are two action-packed parts. But knowing the two bookends well this time around, I paid more attention to this slow part on this viewing, and I enjoyed it. There are artfully composed images of long lines of people going to the pier, some walking on an elevated path while others walk along the foreground. These images reminded me of we would find 20 years later in Ivan the Terrible with its artful lines of people curving into the background and made me think such composition is a part of the Eisenstein film vocabulary. I’ll have to watch for it in other films of his. And as I watched the citizenry of Odessa rise in support of the sailors after viewing Vakulinchuk’s body, I was immediately reminded of a story by Garcia Marquez: "The Handsomest Dead Man in the World." In the story, a body washes up on a beach, and as the villagers begin to take care of it, they become more aware of how they’re living and begin to change their drab, routine world; when the citizens find Vakulinchuk’s body, they too begin to realize the repressive forces that are holding them and begin to move toward renewal. I have to wonder if that most leftist of Latin writers Garcia Marquez saw this most leftist of propaganda films and took this section as a spark for a story. It was great to revisit this film. The new blu-ray release from Kino has some scenes I definitely hadn't remembered, scenes that make the Czarist troops even more vile. I was struck by the brutality of some of the images in the Steps sequence. But I think these scenes just add to the power of this great movie. Watching Battleship Potemkin., again, I enjoyed it again. I like its themes, I like its technique. What a classic.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Monday, October 17, 2011

October 17: House/Hausu (1977 -- Nobuhiko Ohbayashi)

★★★

But the sheer imagination in the film is the element I like the most about it. Not only was I unable to anticipate what would happen from scene to scene, but I couldn’t even anticipate what was going to happen from one moment to the next inside a single scene. When Fantasy discovers Mac’s severed head in the well, the scared girl throws the head back in and quickly turns around to another task. No surprise there. But Mac’s disembodied head then floats out of the well behind the girl and, after a couple of aerial flourishes, descends to the unaware Fantasy and bites her in the ass. Later, the teacher/rescuer horrifies the watermelon farmer by wanting a banana, and when we next see the teacher’s car, the teacher has become a life-sized stack of bananas. House has a staggering inventiveness that never seems to refer to conventional thought.

But the sheer imagination in the film is the element I like the most about it. Not only was I unable to anticipate what would happen from scene to scene, but I couldn’t even anticipate what was going to happen from one moment to the next inside a single scene. When Fantasy discovers Mac’s severed head in the well, the scared girl throws the head back in and quickly turns around to another task. No surprise there. But Mac’s disembodied head then floats out of the well behind the girl and, after a couple of aerial flourishes, descends to the unaware Fantasy and bites her in the ass. Later, the teacher/rescuer horrifies the watermelon farmer by wanting a banana, and when we next see the teacher’s car, the teacher has become a life-sized stack of bananas. House has a staggering inventiveness that never seems to refer to conventional thought.

House is one of the most unique films I’ve ever seen if not the most unique. I think of Japanese culture in general as having a flair for style, but House is style to the nth.

From the moment the film starts with its cute (Spice) Girls saying cute, artificial lines and wearing cute, stylized clothes until the film moves on to the girls’ stylized demises as they are eaten by a lampshade, consumed by a piano or decapitated in a well, House is an outrageous, psychedelic race from one unexpected event to the other. Gorgeous’ father introduces his new fiancé, and the woman is bathed in soft light as her scarf flutters languidly behind her. She almost floats over to her stepdaughter-to-be. The entire movie is one stylization after another.

But the sheer imagination in the film is the element I like the most about it. Not only was I unable to anticipate what would happen from scene to scene, but I couldn’t even anticipate what was going to happen from one moment to the next inside a single scene. When Fantasy discovers Mac’s severed head in the well, the scared girl throws the head back in and quickly turns around to another task. No surprise there. But Mac’s disembodied head then floats out of the well behind the girl and, after a couple of aerial flourishes, descends to the unaware Fantasy and bites her in the ass. Later, the teacher/rescuer horrifies the watermelon farmer by wanting a banana, and when we next see the teacher’s car, the teacher has become a life-sized stack of bananas. House has a staggering inventiveness that never seems to refer to conventional thought.

But the sheer imagination in the film is the element I like the most about it. Not only was I unable to anticipate what would happen from scene to scene, but I couldn’t even anticipate what was going to happen from one moment to the next inside a single scene. When Fantasy discovers Mac’s severed head in the well, the scared girl throws the head back in and quickly turns around to another task. No surprise there. But Mac’s disembodied head then floats out of the well behind the girl and, after a couple of aerial flourishes, descends to the unaware Fantasy and bites her in the ass. Later, the teacher/rescuer horrifies the watermelon farmer by wanting a banana, and when we next see the teacher’s car, the teacher has become a life-sized stack of bananas. House has a staggering inventiveness that never seems to refer to conventional thought.Throughout the film, I tried to get a grasp on where this movie might be coming from. There’s certainly a little of the The Monkees TV show or Sgt. Pepper’s. Some of the more horrific elements echo Monty Python or Dario Argento. But House is one of a kind, and though its consistent tone eventually runs a little slow over the course of 90 minutes, it’s still 90 minutes of some of the most inventive experiment I’ve seen. The perfect Halloween flic.

Later note: Koganada's short, Trick or Truth, adds an important element to an understanding of this film. There's more than just flash to Ohbayashi's work. (http://kogonada.com/portfolio/trick-or-truth)

Sunday, October 16, 2011

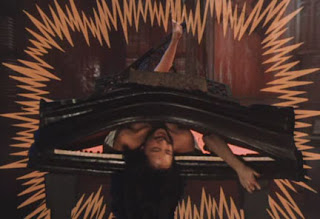

October 16: The Exorcist (1973 -- William Friedkin)

★★★

As part of its serious thrills, Exorcist introduces some great gimmicks. Of course there is the 180-degree head turn, the propulsive vomit, and the jumping bed. And the extended cut I watched included Regan’s backwards spider walk. But some of the creepiest scenes to me were in the medical offices with a jerky x-ray machine popping and waving its arms around and, of course, the blood spurting out of a needle inserted into Regan’s neck. If awfulness like that can exist in the day-to-day natural world, what horrors can lurk in the world of the supernatural? These are effective effects.

As part of its serious thrills, Exorcist introduces some great gimmicks. Of course there is the 180-degree head turn, the propulsive vomit, and the jumping bed. And the extended cut I watched included Regan’s backwards spider walk. But some of the creepiest scenes to me were in the medical offices with a jerky x-ray machine popping and waving its arms around and, of course, the blood spurting out of a needle inserted into Regan’s neck. If awfulness like that can exist in the day-to-day natural world, what horrors can lurk in the world of the supernatural? These are effective effects.

When I saw Scary Movie in 2000, I knew the horror/suspense genre was dead. That film took me right back to graduate school and Northrup Frye’s opinion that irony and parody were the last stages in the vitality of a genre. Frye says you can parody a genre when the audience is so familiar with the conventions that they can recognize them and no longer see the genre as real or vital. Just a form. When the girl in Scary Movie runs from house, sees two arrows – one pointing toward DEATH and the other toward LIFE – and chooses the DEATH direction, I knew that horror had lost its vitality. And in fact, most of today’s horror/thriller/slasher films have an undertone of winks and playing games with an audience who knows the conventions well.

So I enjoyed seeing this movie from before the death of horror, a movie that set so many of the conventions into place and a movie that still generates a few chills. With the leaves almost off the trees here in the Maine woods, Lou and I fixed chili, put comforters on our laps and watched The Exorcist.

The Exorcist has a commitment to horror that is hard to find these days. William Friedkin is making a serious film about real, rounded characters, and the film has high stakes, both philosophically and for the characters. Do we give in to despair when confronting evil, the film asks us. The actors, too, are committed to their characters and bring presence to them in their back story as well as in the immediate action. We understand the conflict and issues that Father Karras faces with respect to his duties as a son and his duties as a priest, and we sense the frailty of Father Merrin from the time we see his early scenes in Iraq. Of course, we spend so much time with Chris MacNeil that we become invested in her struggle as a mother to save her daughter. Such commitment is hard to find in today’s fill-in-the-blank horror films, which have to struggle to even rise to being clever.

As part of its serious thrills, Exorcist introduces some great gimmicks. Of course there is the 180-degree head turn, the propulsive vomit, and the jumping bed. And the extended cut I watched included Regan’s backwards spider walk. But some of the creepiest scenes to me were in the medical offices with a jerky x-ray machine popping and waving its arms around and, of course, the blood spurting out of a needle inserted into Regan’s neck. If awfulness like that can exist in the day-to-day natural world, what horrors can lurk in the world of the supernatural? These are effective effects.

As part of its serious thrills, Exorcist introduces some great gimmicks. Of course there is the 180-degree head turn, the propulsive vomit, and the jumping bed. And the extended cut I watched included Regan’s backwards spider walk. But some of the creepiest scenes to me were in the medical offices with a jerky x-ray machine popping and waving its arms around and, of course, the blood spurting out of a needle inserted into Regan’s neck. If awfulness like that can exist in the day-to-day natural world, what horrors can lurk in the world of the supernatural? These are effective effects.Coming out in 1973, Exorcist couldn’t help but have New Hollywood in it, and it takes aims at social conventions. The church gets its demystification in Karras’, who has become a Jesuit after participating in the Catholic equivalent of ROTC and is having to fulfill his required service. He’s not sure of his faith, and he constantly second-guesses himself for being a priest instead of taking care of his family. The upper-middle class arts crowd gets its come-uppance, too, as we watch the director meanly harass a German servant and see sweet, young, upper class girl transformed into a demon. Religion and class are two favorite New Hollywood targets.

There’s even a self-reflexive element to The Exorcist. Before we see Reagan transformed into monster, we’ve already seen how cinema works as Chris MacNeil practices her lines and hits her numbers in the protest scene Burke is filming. So given these scenes, perhaps The Exorcist isn’t so scary; after all, it’s only a movie.

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

October 12: Dead Man (1995 -- Jim Jarmusch)

★★★★★

The visual beauty of Dead Man is also important to the film. I noticed time and again the tiny depth of field here that is typical of early black-and-white photography, and especially typical of that out West. The focus would be on Depp’s eye, for example, while the rest of his face was slightly blurry. And the rich black-and-white of the film has a 19th century feel. Often, too, the composition of the shots has a still-photo aesthetic, sometimes so stylized as to take you out of the movie in appreciation of how the image looks.

The visual beauty of Dead Man is also important to the film. I noticed time and again the tiny depth of field here that is typical of early black-and-white photography, and especially typical of that out West. The focus would be on Depp’s eye, for example, while the rest of his face was slightly blurry. And the rich black-and-white of the film has a 19th century feel. Often, too, the composition of the shots has a still-photo aesthetic, sometimes so stylized as to take you out of the movie in appreciation of how the image looks.

I love this movie. I’ve thought about it from a lot of different angles, but what I always come back to is that Dead Man has an irreducible quality that makes it more than the sum of the parts that I can identify. The quest of the hero, William Blake, has a “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” quality to it – imaginative and phantasmagorical but with at least a toe in a reality I can recognize but not understand.

There’s the obvious Western movie aspect of Dead Man, and the film fits that genre. Loner William Blake is out on a voyage, and he moves through a country of saloons, gunslingers, powerful businessmen, ambushes, sheriffs, bad guys and Indians. And as the ineffective accountant journeys, he comes of age as a man. It’s right out of John Ford.

But the West Blake finds isn’t in Ford’s Westerns. The trio of bad-guy/bounty hunters tailing Blake includes a black man, killed early, and a reticent cannibal who eats his remaining, more talkative reward seeker. A trio of trappers includes cross-dressing “Sally” Jenko, who regales his companions with graphic descriptions of how Roman emperors tortured Christians; his two big companions fight over who will have the right to rape Blake first, but all three of the trappers end up dead. Blake dines on Sally’s beans and possum.

Dead Man’s Indians have far more complexity and history than the Indians in a typical Western, too. More than the typical Indian guide to the white man, Nobody, is the dominant one of the pair. Nobody saves Blake’s life while steering him through life in the West. This Indian sidekick has a Western education, likes the work of the British poet William Blake, and has even been to Europe as a poster child Native Savage. Dead Man also delivers a striking portrayal of a Northwest Indian village. Jarmush shows the village as a walled fortress with tall, painted walls and large totems, and it has an interior like the casbah of a North African city. The nuance and sophistication of Native American culture comes through clearly in the film.

But there is much more than the Western theme going on in Dead Man. As he journeys though the West, William Blake is also journeying from innocence to experience, citing verses from Blake’s Songs as he goes along. Naïve and tentative at the beginning of the film, the film’s Blake has become capable with a pistol by the end and has learned how to evaluate the risks he faces. He goes from accidental gun-slinger at the hotel to hesitant shooter with the trappers to sophisticated defender of himself and Nobody at the trader/missionary’s post.

There’s also an overlay of language change as Blake moves on this character arc. Early on, Blake voyages to Machine, trusting the words in the letter that promise him a job. In the introductory train sequence, Blake’s fellow passengers dress in more and more rustic clothes as the train moves West until everyone’s in buckskin and slaughtering buffalo out the window. Meanwhile, the train Fireman tries to warn Blake to be cautious, but Blake can’t understand the man’s words; the two clearly have different ideas of what words are and how to use them. Blake is similarly confused by Nobody’s language, partly because of the Indian’s abstract language but partly because Blake still doesn’t understand the West he’s in. Nobody tells Blake that he’ll soon speak with his gun, and Blake soon does so to the two sheriffs who are seeking the reward on Blake’s head. “Have you read my poetry?” Blake asks them before shooting them. By the end of Dead Man, Blake is speaking the nonsense he couldn’t understand at the beginning.

The visual beauty of Dead Man is also important to the film. I noticed time and again the tiny depth of field here that is typical of early black-and-white photography, and especially typical of that out West. The focus would be on Depp’s eye, for example, while the rest of his face was slightly blurry. And the rich black-and-white of the film has a 19th century feel. Often, too, the composition of the shots has a still-photo aesthetic, sometimes so stylized as to take you out of the movie in appreciation of how the image looks.

The visual beauty of Dead Man is also important to the film. I noticed time and again the tiny depth of field here that is typical of early black-and-white photography, and especially typical of that out West. The focus would be on Depp’s eye, for example, while the rest of his face was slightly blurry. And the rich black-and-white of the film has a 19th century feel. Often, too, the composition of the shots has a still-photo aesthetic, sometimes so stylized as to take you out of the movie in appreciation of how the image looks.Such self-consciousness is a big part of the aesthetic of the film. In addition to the occasional over-the-top images and the cross-dressing trapper, Dead Man has the most Caucasian Indian you’ll see in Gary Farmer’s Nobody. Robert Mitchum’s long monologue with his back to the camera makes you aware of the camera, and the intercutting of the train wheels with the passengers’ changing dress highlights the filmic in Dead Man. And there is Neil Young’s eerie, interpretive, intrusive, improvised soundtrack throughout. Artifice is integral to the film.

What all this leads to, in the words of Roger Ebert’s infamous review, I don’t know. But I was mesmerized and touched by Dead Man. I don’t what I thought as William Blake was pushed off in his funerary canoe and his right-hand man and arch nemesis killed each other in the background, but it was a feeling of wonder. The significance of Blake’s voyage is just out of my reach. I can see a lot of parts in this film and many levels of significance, but all these elements ultimately lead to something bigger than the sum of the parts. Beauty, perhaps.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)